Story by Becca Castellano

USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs

STUTTGART – When COVID-19 began its rapid spread around the globe, it brought with it a whole new set of rules to live by. From physical distancing to obsessive hand washing routines, and the new normal of mask wearing, the virus changed our existence in a matter of weeks. But for those in older generations, COVID-19 is not the first time they have had to stay home for fear of spreading dangerous germs.

From 1916 until 1955, late summer was known as Polio Season. Swimming pools would close and movie theaters would spread guests out to avoid close contacts. Special “polio insurance” was sold to protect newborns as one of the most feared viruses in history began its annual spread across the nation.

Back then, the term “Iron Lung” was well known. Nurses patrolled playgrounds, offering cold milk on ice to lure mothers and children in and observe them for symptoms of polio. If any were present, they could take that child away from their parents to be quarantined in a hospital ward.

Dr. Barabara Roper is a clinical pharmacist at the U.S. Army Health Clinic Stuttgart, and a child of the polio era. While she was not old enough at the time to remember the worst of the virus, she recalls the mission to eradicate it once a successful vaccine was developed.

“It was a very interesting time because parents, who didn’t know a lot about it, were bringing their kids in to be immunized. We would take it on a sugar cube,” said Roper. “We had a vaccine but [Polio] was still on the map at that time.”

The polio vaccine was developed in 1955 and by 1962, polio’s presence in the world was reduced by 90 percent. By the end of the decade, the most feared virus of the 20th century was more of a faint memory for most.

“The herd got vaccinated and that was what was beneficial with polio,” said Roper. “Enough people were willing to get vaccinated that they greatly reduced the spread of the virus long enough to get it under control.”

65 years later, the herd is being asked to get immunized again in the fight against COVID-19, and Roper believes strongly in the science behind the mission.

“We know how to make vaccines and we’ve been doing it successfully for a long time now,” she explained. “We’re going to put something into the body, that is not live – so you are not going to really get it – but it can still stimulate the immune system to create a response so that if that virus comes again, it says ‘hey I know that and we need to push that out of here.”

Roper also said that despite what many believe to be a quick turnaround, it is common for medicine to hit the market as fast as the COVID-19 vaccines did.

“Drugs get fast-tracked a lot,” she explained. “Especially if we already know a lot about them or we start seeing results that are overwhelmingly positive. They will actually stop a clinical trial in the middle of it when the data is so robust that it says hey go for it, we need to use this.”

Katalin Kariko was a scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, who refused to give up on what most in the scientific community deemed a far-fetched idea, Messenger RNA. After nearly a decade of trial and error, and a demotion for a lack of progress on her research, she finally discovered a break-through that would ultimately lead to the development of both Moderna and BioNTech startups – the latter of which would go on to hire Kariko as their Senior Vice President.

Since BioNTech’s start in 2008, and Moderna’s in 2010, the two companies have been experimenting with several uses for mRNA technology, including the concept of custom cancer vaccines. The point, according to Roper, is that the research wasn’t rushed. It began long before the new coronavirus mutated and began infecting humans.

“There’s a lot of people out there already doing research so they already had background information about this through clinical trials,” said Roper. “Thats why they could get to work and come up with a solution so fast. If it were an idea that they had to generate from step one, it would take much longer.”

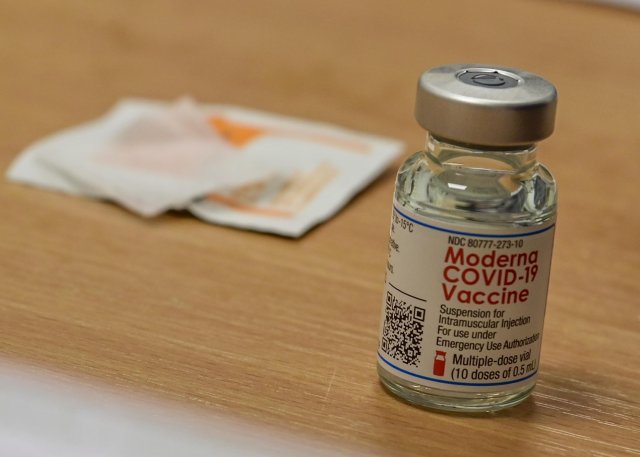

When the first doses of the Moderna vaccine were offered to health care and emergency services workers at USAG Stuttgart on Dec. 31, 2020, Roper was one of the first in line to take the jab.

“I really, truly believe in it,” she said. “30,000 people received the vaccine in the trials, that’s a lot of people. So, if you look at the number of people that had a very negative outcome, it was not large.”

Despite her confidence, she understands why others may be cautious due to all the sensationalism and misinformation out there. She urges everyone to check their sources and to reach out to their primary care provider or pharmacist to get guidance and answers.

“They can help you determine what’s best for you,” she said, adding that pubmed.gov is a credible source where all clinical trials are published.

Despite her pro-vaccination belief, Roper respects every individual’s right to decide what is best for themselves and strives to provide clear, honest guidance to her patients.

“That’s what pharmacists do, we talk about side effects and give you all the information so you’re well prepared,” she said. “Because we don’t want people to be frightened when anything they weren’t expecting happens.”

Some of the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine can be soreness, redness and warmth at the injection site said Roper. She added that a small population reported experiencing flu-like symptoms and felt lousy for a few days and admitted to having a headache herself for a day or two after receiving her first dose.

“You may get a response to it but that’s your body doing its job and now you’re going to be prepared and you can fight it off when it comes again,” said Roper. “Yes, there’s a risk that you could be that person who gets a negative reaction. But that’s why we screen on the immunization forms and we ask questions before you get it.”

As a clinical pharmacist, Roper has a continuously evolving knowledge of more than 5,000 drugs on the market and an understanding of how they interact with each other. She is always reading, researching, and learning, to help patients with conditions like diabetes, high-blood pressure, hypertension and asthma, live healthier lives. Now she hopes to use that knowledge to help those afraid of COVID-19, understand the facts and make an informed decision.

“In 2000, when my daughter was born, the autism scare around vaccines was still a hot topic, and so much of that came of published false information. The aftermath was very negative,” Roper said. “That affected a lot of people, but I had a great provider who answered my questions and gave me the real facts, and that changed the dynamics for me. That’s what I always aim to do. Just provide the facts.”

But in a time when facts are far fewer and speculation runs rampant, Roper said she continues to read the research, study the clinical trials, and learn from history.

“I just come back to what we know. Polio was devastating, I mean, people were in iron lungs. It was really scary. Yet, we all but eradicated it through immunizing the herd,” said Roper. “And now we have to do it again. This is how we protect those who are immunocompromised. At the end of the day, the benefits far outweigh the risks.”