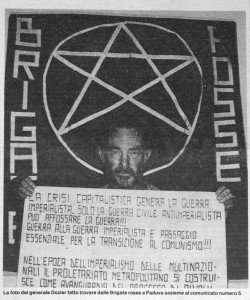

Brig. Gen. James L. Dozier was kidnapped by Red Brigade terrorists in December 1981. The high-profile kidnapping is a scenario known to many in and around the military and frequently the subject of antiterrorism training for most services.

By Sgt. Daniel Cole

U.S. Army Europe Public Affairs Office

Terrorist tactics may have changed over the years, but U.S. Army Europe force protection experts say one thing will always stay the same — remaining vigilant for the signs of terrorist activity can help stop the bad guys in their tracks.

One example that happened within the Army in Europe is the kidnapping of Maj. Gen. James Dozier from his home in Verona, Italy, in December 1981.

Dozier, then deputy chief of staff for the Southern European Task Force, was abducted by the Red Brigade terror group and held captive for 42 days before being rescued. Three years earlier the group had kidnapped former Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro and kept him captive 55 days before murdering him.

The Red Brigade had considered several U.S. general officers for abduction, but ultimately selected Dozier. Force protection officials say the factors influencing his selection included his status as a senior leader, lax personal security and predictable patterns of behavior that facilitated the terrorists’ attack.

The kidnappers conducted surveillance on Dozier’s apartment prior to the attack, a common tactic used to gather information for target selection and attack planning. Group members often stood at a nearby bus stop for long periods, staring at the general’s apartment. The watchers rarely got on a bus, or would sometimes ride the bus, but get off at the same stop in front of the apartment a short while later.

On two occasions, a pair of terrorists posed as utility meter readers to gain access to Dozier’s apartment. Force protection officials said this should have aroused suspicion, because in Italy it is unusual for a utility company to send two workers to perform this task.

Unfortunately, no one picked up on these signs of the suspicious behavior displayed by Dozier’s stalkers. After a month of being watched he was kidnapped and taken to an apartment in Padua.

Force protection officials said Dozier later admitted that he did not take the terrorist threat seriously and was lulled into an “it can’t happen here” mind-set.

While this incident is more than 30 years old, antiterrorism experts say it still provides valuable lessons and reminds Americans in Europe that there are real threats. They offered a few pointers that can help people avoid becoming targets: be vigilant for suspicious or abnormal behavior; become familiar with local culture and habits; vary travel times and routes to become less predictable to terrorist or criminal elements; and confirm the identities of workers or other visitors before granting them access to homes or workplaces.

Most of all, the experts advise members of the Army in Europe community to report suspicious activity using the iWatch and iReport links found on all Army home pages in the theater or go to the USAREUR reporting site athttp://www.eur.army.mil/eureport .