By John Reese

By John Reese

USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs

September is Suicide Prevention Month, and with it comes greater awareness that there are friends, comrades and family members who may be considering that irreversible decision.

There are many behavioral indicators to look for if you suspect someone is considering suicide. Some are direct while others are subtle enough to be missed until it is too late. The garrison’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP) and Army Substance Abuse Program (ASAP) have teamed up this month to enhance awareness, beginning with a resource table and cake cutting at the Panzer Kaserne Exchange Sept. 7, beginning at 10:30 a.m.

“This is a time for sharing and caring to support service members, veterans and civilian families who have lost their loved ones,” said Dr. Kaffie Clark, EAP coordinator. “Volunteers will be giving out yellow ribbons at the Panzer Kaserne main gate, 7-9 a.m., Sept. 11 and 13, to remember our loved ones, our Soldiers and those who lost their lives.”

Clark and Cinda Robison, ASAP prevention coordinator, have access to the most recent Army suicide statistics, giving them a bigger picture of the severity of military suicides for briefing commanders.

Robison shared a story about meeting a young Soldier who was behaving in a peculiar manner, allowing others again and again to pass her in a line halfway through a common task. When Robison commented on the Soldier’s patience, the person opened up and explained how a recent PCS and other factors had caused extreme exhaustion.

“Sometimes it isn’t the usual signs (giving away valuables, putting affairs in order, loss of enthusiasm and hope, etc.) when a person is considering suicide,” Robison said.

A scholarly study, sponsored in part by the Department of the Army for and published July 26 in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), found that previous suicides in a unit increased the chances of a Soldier committing suicide, particularly with smaller units. The study used information from the “Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers” and focused on “all active-duty, regular U.S. Army, enlisted Soldiers who attempted suicide from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2009.”

During that time frame, the study found that of “the 9512 enlisted suicide attempters … most were male (86.4 percent), 29 years or younger (68.4 percent), younger than 21 years when entering the army (62.2 percent), white (59.8 percent), high school educated (76.6 percent, and currently married (54.8 percent). Almost three-quarters (72.2 percent) had more than 2 years of service, 40.3 percent had never deployed, and 76.7 percent were assigned to an occupation other than combat arms.”

The highly-detailed study indicated the risk of suicide attempts (SA) among Soldiers is influenced by a history of SAs within a Soldier’s unit.

“Attention to unit characteristics by leadership and service professionals may be a component in SA reduction efforts. Early unit-based postvention consisting of coordinated efforts to provide behavioral, psychosocial, spiritual, and public health support after SAs may be an essential tool in promoting recovery and suicide prevention in servicemembers,” read part of the study’s conclusion.

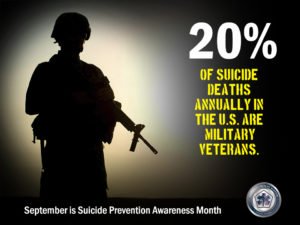

Veterans and suicide

Suicides disproportionately affect veterans, Clark and Robison noted. They pointed to a Veterans Affairs statistic from 2013 on the suicide rate among veterans. Four years ago, veterans were committing suicide at a rate of 22 per day, or one every 65 minutes. As shocking as that number was, that study represented only 21 states; the two largest and fifth largest states didn’t provide data to the VA for the survey.

Common knowledge from the 2013 report indicates the number of 22 per day didn’t reflect the actual number of veterans who died by suicide, Clark said.

“It’s huge, the discrepancy,” Robison added. “It could’ve been as high as 35 suicides per day.”

Since 2013, the number of recorded veteran suicides has declined a little. A VA report in 2016 using analysis from 2014 put the average at 20 per day, or one every 72 minutes.

On July 26, the same day the JAMA study was published, CNN interviewed retired Army physician assistant Maj. Marc Raciti, who came very close to hanging himself after five deployments.

“I did lose three medics after coming back from Iraq to suicide, which exasperated my PTSD, but mine is of survivor’s guilt for the ones I could not save,” he said during the interview.

In August, VA Secretary Dr. David Shulkin spoke about a new and disturbing trend of veterans coming to a VA facility to commit suicide.

“There are a number of reasons (for coming to the VA to commit suicide), not all of which I completely understand,” Shulkin said, adding one of the reasons is “they don’t want their families to have to discover them. They know that if they’re discovered at a VA, that we will handle it in an appropriate way and take care of them.”

According to Clark and Robison, helping to prevent suicides in the Stuttgart military community is everyone’s job. As Stuttgart is a joint service community with many civilians and family members, suicide prevention should be practiced by everyone regardless of branch, age or veteran status.

According to Clark and Robison, helping to prevent suicides in the Stuttgart military community is everyone’s job. As Stuttgart is a joint service community with many civilians and family members, suicide prevention should be practiced by everyone regardless of branch, age or veteran status.

“Another event to help bring awareness will be the Celebrate Life Coffee Giveaway, Sept. 18, at the Panzer Exchange,” Clark said. “After that, there will be an ASIST (Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training) workshop offered Sept. 26-27.”

A message from Dr. Keita Franklin, director, Defense Suicide Prevention Office

“Every suicide is a tragic loss to our nation and those impacted. The family and friends left behind who must deal with the aftermath of the event and put those events in perspective, may in some cases never know why the service member or veteran took their life. Suicide is the culmination of complex interactions between biological, social, economic, cultural and psychological factors operating at the individual, community and societal levels. We are committed to fostering collaboration and cooperation to develop suicide prevention efforts among all stakeholders including the military services; federal agencies; public, private, international entities, and institutions of higher education.”

Who to call and learning to ASIST

For help, call DSN: 431-2530 or the Military Crisis Line at DSN: 118 or 0800-1275-8255.

Recognize opportunities to prevent suicides by becoming a primary or secondary “Gatekeeper.” Attend an Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training workshop, 9 a.m. – 4:30 p.m., Sept. 26-27, at Panzer Chapel. Call 431-2743 to learn more about Gatekeepers.

ASIST has undergone extensive evaluation in Australia, Canada, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Norway, Scotland and the United States. Further evaluation information can be obtained on the LivingWorks website at www.livingworks.net.