The National Defense Authorization Act passed last month requires sweeping changes to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, particularly in cases of rape and sexual assault.

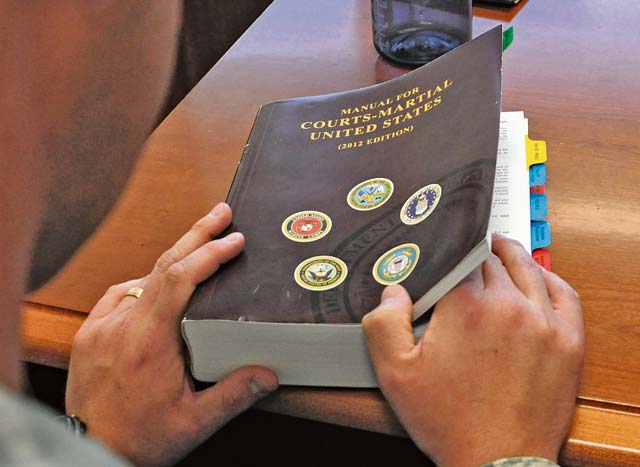

“These are the most changes to the Manual for Courts-Martial that we’ve seen since a full committee studied it decades ago,” said Lt. Col. John L. Kiel Jr., the policy branch chief at the Army’s Criminal Law Division in the Office of the Judge Advocate General.

Key provisions of the UCMJ that were rewritten under the NDAA are Articles 32, 60, 120 and 125.

The National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2014 has brought sweeping changes to the Manual for Courts-Martial.

Article 32

The law now requires the services to have judge advocates serve as Article 32 investigating officers. Previously, the Army was the only service in which judge advocates routinely did not serve as Article 32 investigating officers.

Article 32 hearings ― roughly equivalent to grand jury proceedings in the civilian judicial system ― are held to determine if there’s enough evidence to warrant a general court-martial, the most serious type of court-martial used for felony-level offenses such as rape and murder.

Congress decided that the services needed to have trained lawyers ― judge advocates ― consider the evidence, since in their view, trained lawyers often are in the best position to make determinations to go forward with general courts-martial, Kiel said. Judge advocates didn’t always serve as Article 32 investigating officers in the Army “largely because we try four times the number of cases of any of the other services,” he explained ― an issue of not having enough judge advocates for the high volume of cases.

Army officials asked Congress to consider its resourcing issue, he said, so the legislators wrote an exception, stating that “where practicable, you will have a judge advocate conduct the Article 32 investigation.”

The 2014 NDAA gives the services one year to phase in this change to Article 32. This one-year time period provides needed time for the staff judge advocates to figure out if they have enough judge advocates to fill the requirement to cover down on all the Article 32 hearings and determine which installations are struggling to meet the requirements, Kiel said.

Another impact to courts-martial practice is the new requirement for a special victims counsel to provide support and advice to the alleged victim, Kiel said. For example, the special victims counsel must inform the victim of any upcoming hearings ― pretrial confinement, parole board, clemency and so on ― and inform the victim that he or she can choose to attend any of those. The victim also will be notified in advance of trial dates and be informed of any delays.

Furthermore, Kiel said, the special victims counsels may represent the alleged victims during trial, ensuring their rights are not violated, as under the Rape Shield Rule, for example. The Rape Shield Rule, or Military Rule of Evidence 412, prevents admission of evidence concerning sexual predisposition and behavior of an alleged victim of sexual assault.

Kiel provided an aside regarding the Rape Shield Law and how a high-visibility case a few months ago involving football players at the U.S. Naval Academy influenced changes to Article 32 by Congress.

In that case, the defense counsel had the victim on the stand for three days of questioning about the alleged victim’s motivations, medical history and dress during the Article 32 hearing, he said. The cross-examination was perceived by the public and Congress to be disgraceful and degrading, and potentially violating the federal Rape Shield Rule. With passage of the fiscal 2014 NDAA, alleged rape and sexual assault victims are no longer subject to that kind of interrogation at the Article 32 hearing, he said.

Before the new law, alleged victims of sexual assault were ordered to show up at Article 32 hearings and frequently were asked to testify during those hearings as well.

“Congress thought that wasn’t fair, since civilian victims of sexual assault didn’t have to show up or testify,” Kiel said.

“Now, any victim of a crime who suffers pecuniary, emotional or physical harm and is named in one of the charges as a victim does not have to testify at the hearing,” he added.

Article 60

Article 60 involves pretrial agreements and actions by the convening authority in modifying or setting aside findings of a case or reducing sentencing. A convening authority could do that in the past, and some did, though rarely.

Changes to Article 60 were influenced last year by a case involving Air Force Lt. Col. James Wilkerson, a former inspector general convicted of aggravated sexual assault, Kiel said. The convening authority, Air Force Lt. Gen. Craig Franklin, overturned the findings of guilt.

“That got Congress stirred up,” Kiel said.

In the new law, legislators said the convening authority can no longer adjust any findings of guilt for felony offenses where the sentence is longer than six months or contains a discharge. They cannot change findings for any sex crime, irrespective of sentencing time.

Prior to the new law, the convening authority could consider the military character of the accused in considering how to dispose of a case, Kiel said. Congress decided that should have no bearing on whether or not the accused has committed a sexual assault or other type of felony.

Also, he said, previous to new law, “sometimes the [staff judge advocate] would say, ‘Take the case to a general court-martial,’ and the convening authority would disagree and say, ‘I’m not going forward.’” Now, he said, “if the convening authority disagrees, the case has to go to the secretary of the service concerned, [who] would have to decide whether to go forward or not.”

In the case of an alleged rape or sexual assault in which the staff judge advocate and the convening authority decide not to go forward because of a lack of evidence or for any other reason, that case has to go up to the next-highest general court-martial convening authority for an independent review, Kiel said. So if the case occurred at the division level in the Army, for example, and a decision were made at that level not to go forward, then the division would need to take the victim’s statements, its own statements for declining the case, and forward them and the entire investigative file to the next level up ― in this case, the corps. At the corps level, the staff judge advocate and the corps commander would then review the file, look at the evidence and make a determination whether or not to go forward, Kiel explained.

If it’s decided to move forward, the case would be referred at the corps level instead of sending it back down to the division, he added. This, he explained, avoids unlawful command influence on the case’s outcome.

Articles 120 and 125

Articles 120 and 125 now have mandatory minimum punishments: dishonorable discharge for enlisted service members and dismissal for officers, Kiel said. Article 120 deals with rape and sexual assault upon adults or children and other sex crimes, and Article 125 deals with forcible sodomy. In addition, the accused now must appear before a general court-martial with no opportunity to be tried at a summary or special court-martial, Kiel said. A summary court-martial is for relatively minor misconduct, and a special court-martial is for an intermediate-level offense.

Furthermore, Congress highly encouraged the services not to dispose of sexual assault cases with adverse administrative action or an Article 15, which involves nonjudicial punishment usually reserved for minor disciplinary offenses, Kiel said.

Kiel said Congress desires those cases to be tried at a general court-martial and has mandated that all sexual assault and rape cases be tried only by general court-martial.

Prior to the fiscal 2014 NDAA, there was a five-year statute of limitations on rape and sexual assault on adults and children under Article 120 cases. Now, there’s no statute of limitations, he said.

Congress repealed the offense of consensual sodomy under Article 125 in keeping with previous Supreme Court precedent, Kiel said, and also barred anyone who has been convicted of rape, sexual assault, incest or forcible sodomy under state or federal law from enlisting or being commissioned into military service.